A Tale of Two Fictions: An "American Fiction" Review

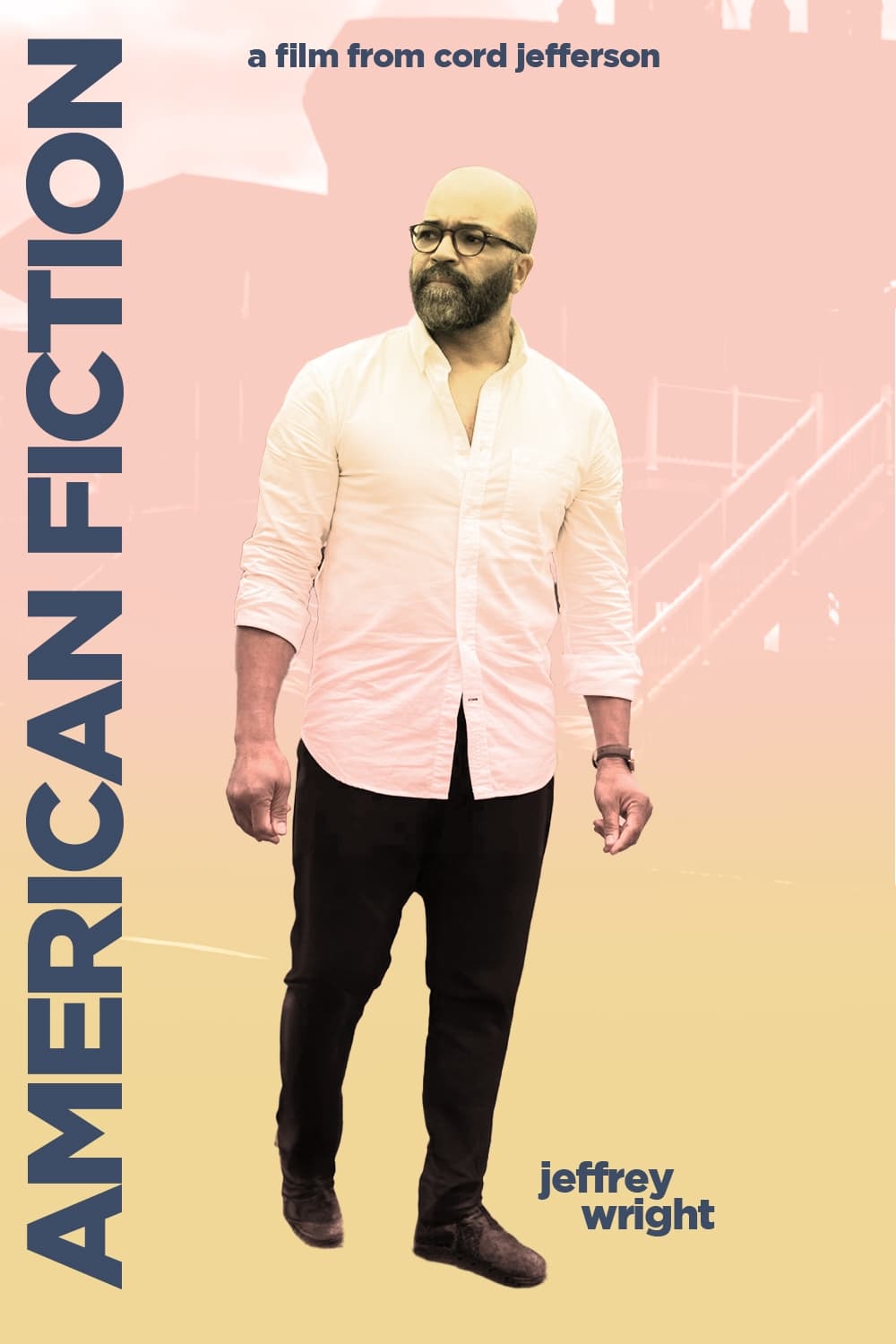

Cord Jefferson's debut feature film opens on Thelonious Ellison, played by Jeffrey Wright (The Batman, The French Dispatch), instructing a southern American literature class at a university. The viewer sees a large whiteboard, with domineering text that describes a character trope through the use of a racial slur. A white student interrupts the class to object to the use of slurs in the teaching of key texts in the unit, disregarding the professor's insistence that the use of the language is integral to understanding the text of the era and to understanding how literature and language develop. The white student claims that the language makes her uncomfortable, while Ellison tells her to get over it. After a hard cut, Ellison is put on a forced sabbatical. It's a wonderful cold open, hitting on some of the film's most poignant themes; black stories and literature being told with white comfortability and fragility in mind, the risk of ostracization for not following the single story (See: "The danger of a single story" by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie) of the modern African American, and foreshadowing a plenty to prep the viewer for the cultural critique of the next two hours. The film cuts to opening credits, and we hardly see that level of concise storytelling again.

Consistency is the main thing that American Fiction struggles with. Between the advertised story of Ellison going unappreciated for his prose, due to its themes and plots not aligning with the expected narratives of his skin pigment, is a grounded family drama outlining recent turmoil in Ellison's family dynamic. The purpose of this coexisting storyline is to showcase Ellison's deviation from the expected singular story of the black experience in America.

Devoid of life-changing experiences with racism, Ellison lives as the child of an affluent family of doctors who must grapple with the failing health of their mother while resolving conflicts leftover from both new and old history. It's tragic, sweet, and entirely mundane in its presentation, intentionally so. It gives an amazing contrast to Ellison's fake life as Stagg R. Leigh, the pseudonym/fake identity that he plays for publishers and producers in the film's other plotline. Stagg is a claimed fugitive whose goal is to give a voice to the incarcerated black population through his own real lived experiences in his book, semi-satirically titled "Fuck."

This setup would leave one to believe that they're in for a clashing of worlds, a reckoning between the two lives which Ellison is living, one in which he is himself and where his biggest struggles come from his mother's encroaching Alzheimer's, and one that fits into the narrative of the disadvantaged and beaten down African American who isn't allowed to succeed in a system not built for him. In reality Ellison is successful, he thrives in the institutions in which he participates (if not commercially, then in artistically), it's not a denial of the reality of racism prevalent in America, but a showcase of living successfully in spite of that reality, it's empowerment through success.

However, that reckoning of worlds never comes. In fact, the scenes of Ellison dealing with the lie of Stagg R. Leigh and the scenes of Ellison dealing with his family troubles are almost entirely separated. Going from one plotline to the other feels like the viewer is being treated to two different films, neither of which are given the time and consistent presentation to really leave you with anything satisfying to take away. This leaves the viewer scratching their head at which of these two narratives is supposed to be the focus of the film; both narratives are the focus of the film, but at the same time neither succeeds in coming to a conclusion befitting its subject matter.

That's not to say that the film is entirely floundering in trying to reconcile its competing plotlines. In a scene between Ellison and his love interest, Ellison berates her for enjoying the book he wrote as Stagg, unable to be fully truthful to her about his secret identity. In another where Ellison is judging the winners of a literary awards show, three of the white judges who love Stagg's book want to choose it for the first-place prize, while the two black judges (including Ellison) find the book to be pandering and undeserving of even being placed. This leads to a beautifully ironic moment of the white judges on one side of the room telling the black judges, juxtaposed on the opposite side of the room, that they need to "listen to black voices."

Great moments like this rear their head throughout the film, bringing together a perfect storm of themes, cinematography, and acting, but the director is unable to imbue the satisfaction of those moments onto the entire film, leaving the viewer confused as to what the actual point of the whole narrative was; is it a cultural critique on race in America, or a mundane New England family melodrama. Each plot feels supplemental to the other, without either being present enough to command the viewers attention.

Individual elements of the film are very enjoyable. Wright brings a wonderful comedy to the film with his portrayal of Ellison as a hard-headed, emotionally unavailable pushover, he's the glue which brings many of the film's best jokes together. Sterling K. Brown (Black Panther, Waves) as Ellison's brother Clifford, a recently out and divorced gay man, is another wonderful addition to the cast. He pulls off both comedic relief and dramatic catalyst with amazing range, even with the limited screentime and character development granted to him.

Similarly, the film's score is used to great effect to create an exciting fast pace that propels the first act into an entertaining collage of failure and tragedy which leads to the inciting incident of the film. It's a mix of clubhouse jazz and adult contemporary, elegant and understated to compliment the affluent yet chaotic life of the main cast. To the directors credit, the score is used to appropriately convey the emotion of the scene, fast and chaotic drums and trumpets to underscore Ellison falling into his million dollar Stagg R. Leigh lie, and quiet and comical when we switch to the family scenes. Once again it works well on a scene-by-scene basis, but in the context of the whole film this element comes off as tumbling towards, and falling short, of emotional and tonal consistency.

"American Fiction" is a rare case of a director knowing exactly the kind of film they want to make but can't quite make it come together. The narratives end up lacking in the competency that makes a film come together in a realized vision, and instead leaves the viewer with moments of thematic satisfaction marred by clumsy execution. There are motifs and gimmicks used once and never brought up again. There are multiple scenes and subplots which are well executed removed from the rest of the film, but unimportant in the larger narrative. And there's a somewhat baffling ending resembling Robert Altman's "The Player" to confusing effect. While there are hints in the film to director Cord Jeffersons poignantly original social commentary, this film unfortunately leaves any realization of that commentary in the realm of fiction.

Written by: Aliena Abernathy

Published: 1/9/2024